A decade ago ArtNews Magazine described Ilya Kabakov as one of the world’s 10 greatest living artists. In collaboration with his wife, fellow artist Emilia Kabakov, their installation “The Strange City” was selected as the Monumenta 2014 exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris this past May.

According to their official biographical sketches: “Ilya and Emilia Kabakov are Russian-born, American-based artists that collaborate on environments which fuse elements of the everyday with those of the conceptual. While their work is deeply rooted in the Soviet social and cultural context in which the Kabakovs came of age, their work still attains a universal significance.

|

|

The model for the Kabakov “Ship of Tolerance” installation, which is actually 20×7 meters in size and is used as a tool to teach tolerance with the sail on the 13 meter mast formed by school children’s messages and paintings on the subject. (Photo: Kevin D. Morris for Hamptons.com) |

Ilya Kabakov was born in Dnepropetrovsk, Soviet Union, in 1933. He studied at the VA Surikov Art Academy in Moscow, and began his career as a children’s book illustrator during the 1950’s. He was part of a group of Conceptual artists in Moscow who worked outside the official Soviet art system. In 1985 he received his first solo show exhibition at Dina Vierny Gallery, Paris, and he moved to the West two years later taking up a six months residency at Kunstverein Graz, Austria. In 1988 Kabakov began working with his future wife Emilia (they were to be married in 1992). From this point onwards, all their work was collaborative, in different proportions according to the specific project involved. Today Kabakov is recognized as the most important Russian artist to have emerged in the late 20th century. His installations speak as much about conditions in post-Stalinist Russia as they do about the human condition universally.

Emilia Kabakov (nee Lekach) was born in Dnepropetrovsk, Soviet Union, in 1945. She attended the Music College in Irkutsk in addition to studying Spanish language and literature at the Moscow University. She immigrated to Israel in 1973, and moved to New York in 1975, where she worked as a curator and art dealer.

Their work has been shown in such venues as the Museum of Modern Art, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Documenta IX, at the Whitney Biennial in 1997 and the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg among others. In 1993 they represented Russia at the 45th Venice Biennale with their installation The Red Pavilion. The Kabakovs have also completed many important public commissions throughout Europe and have received a number of honors and awards, including the Oscar Kokoschka Preis, Vienna, in 2002 and the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres, Paris, in 1995.”

For the past two decades the Kabakovs have lived and worked from their home and studios in Mattituck on Long Island’s North Fork. Hamptons.com had the privilege to visit the grounds and speak with the artists. Their answers to our questions, like their art, was collaborative.

Was there a particular event early in your lives that evoked the desire to create art or was there just an inherent ability and temperament that made your artistic paths inevitable?

Kabakovs: Interesting question! I think it’s just the ability to dream, to fantasize, not to be very interested in reality, always trying to create another realm, by storytelling, by paintings, by playing music, writing poetry. It’s just…too much creativity.

|

|

Hamptons.com Senior Contributing Editor Douglas MacKaye Harrington honored to be in the presence of Emilia and Ilya Kabakov in front of Ilya’s latest work-in-progress. (Photo: Kevin D. Morris for Hamptons.com) |

Ilya, art in the Soviet Union at the time you began your career was “officially” sanctioned and you became, reluctant or not, a member of the Union of Soviet Artists. It benefited you financially and sustained you as an artist, but did it also create limited parameters for your artistic expression?

Kabakovs: A lot of artists were members of the artistic union. It gave you the possibility to buy paints, canvases, brushes, even the possibility to get a studio if you had the money to build it. It also gave you the possibility to make your living by making official art and then you would get a lot of “official” commissions: portraits, paintings, murals, etc. Skipping this possibility would restrict your creative process to very official controls, you could illustrate books, political or children’s books. Many artists choose this road as the most invisible, safest and even profitable, even though paintings would probably bring more money. This was done by Malevich, and all the others. Don’t believe Wikipedia, not everything written there is true. The Soviet Artists Union was not a communist party organization. It was a professional union, which did not protect you from the government if the government decided you were the enemy, but it did give you the possibility to work in your profession and survive.

Ilya, you existed for many years as an artist of duality, illustrating books as a sanctioned artist and creating works for yourself as an unsanctioned artist, eventually losing your illustration commission for four years due to the “Shower Series” drawings exhibited in Italy. Was this a significant turning point in your career as you continued to create, but often under aliases? In other words, did it foster a sense of defiance in you that was reflected in your art?

Kabakovs: “The Shower Series” was an act of defiance already. By that time the characters already were created in the albums, so that was just a very dangerous and extremely inconvenient situation, but thanks to some good friends I was still illustrating children’s books, under the name of an artist’s friend.

|

|

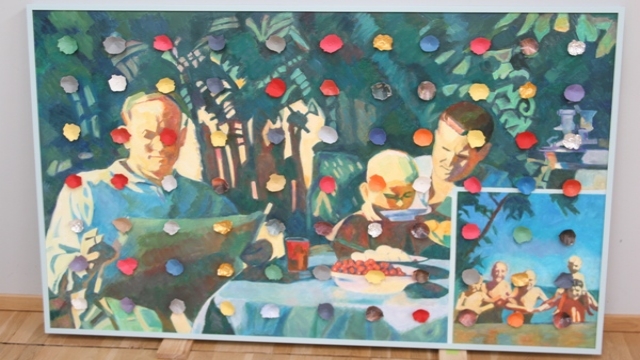

Ilya Kabakov’s “Holidays #10” (1987) sold for $2.4 million at Phillips de Pury & Co. in London in 2011. (Photo: Kevin D. Morris for Hamptons.com) |

Your early works, and even today, were fused with textual accompaniment and a dominant singularity of color, often earthen in hue, is there a specific significance to these choices or do they simply reflect your artistic style and taste in medium?

Kabakovs: Of course this is an artistic choice and there is significance to the choices. I use text because I do use narrative, which is very important to Russian literature and I would say Russian art as well is especially conceptual art. As for the colors, the colors I used before are the colors reflecting on the drabness, bureaucracy, banality of everyday Russian life. Now, I do use a much larger spectrum of colors in my paintings.

Emilia, your artistic journey certainly was different from Ilya’s, as you immigrated to Israel in 1973 and then on to New York two years later. Please elaborate and do you feel your collaboration with Ilya brought a different perspective that honed the installations and other works created as a couple?

Kabakovs: I was a musician and my relationship with art was purely visual. I visited Ilya’s studio in Moscow, had a lot of artist friends, but music was my priority and my life. Then for many reasons I became interested in art and by the time Ilya came to the west I was already very involved. I can say I learned installation art from Ilya, all the nuances, all the subtleties of creating the installation as an art form, especially total installation took years. As for how we work, I really cannot explain this process. In order to understand this you really have to spend time with us during the installation period, at home when we work on the idea, on the concept, on the technical details. And then you will ask me the same question and I probably will give you the same answer.

|

|

Kabakov installations incorporate the mediums of painting, music, literature, architecture and sculpture like these three models of Ancient Greek Gods. (Photo: Kevin D. Morris for Hamptons.com) |

Let us take one of your seminal works and let you both describe its intention and meaning: “The Red Wagon.”

Kabakovs: “Red Wagon” is one of the best examples of total installation. Outside it’s a sculpture, which is a metaphor of the whole history of the creation and development of the Soviet Union: wagon without wheels, going nowhere. The ladder represents the beginning of Soviet time: promised utopia, dream of building the new world, going up, the ladder taking us to the sky, to another dimension. Then you have to go around, looking at the “happy paintings” depicting all the achievements and happiness of people living in this paradise. The front door is closed and at the back is typical distraction, disarray, piles of garbage. You walk inside, dark, very intimate atmosphere with sentimental music from the 1950s, and a huge panel on the wall showing the viewer this beautiful world, with blue sky, new buildings, airplanes, but no people there. The future and this promised paradise is not for us, not for you. It’s for them and you just sit there, unable to leave, because this vision, this light coming from below the barrier, this music holds you a prisoner to your own memories and fantasies. As I said, the perfect example of total installation.

Ilya, you are credited as both one of the most important 10 living artists and probably the greatest living Russian artist, albeit now working in America since 1992, and your work remains a commentary of and highly influenced by your Soviet experience and background. Do you consider your art cultural reflection or political commentary, or neither?

Kabakovs: Definitely a cultural reflection! A human commentary on fears, fantasies, dreams and phobias of regular, everyday people who could be from any country which would have a similar political structure, totalitarianism.

Furthermore, as Ukrainians by birth and artists that fled the artistic repression of the Soviet Union, what do you make of the events unfolding in the Ukraine and might we expect a Kabakov version of “Guernica” as an installation in response?

Kabakovs: If we say “yes” to this question or even “no” that would be a political commentary. We will see!

|

|

The model for one of the seven rooms that made up the Monumenta 2014 installation was actually the size of the Kabakov studio pictured below. (Photo: Kevin D. Morris for Hamptons.com) |

Your recent Monumenta exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris is certainly a milestone; please elaborate on the installation and the significance of this extraordinary honor.

Kabakovs: Well, this is a next and a very big step on the ladder in the art world, art history, and it gives us a possibility to create the biggest and one of the most important installations we ever did. We build “The Strange City” in the Grand Palais, one of the most important places in the art world where the first salon of contemporary art in Paris took place. This labyrinth of inside and outside spaces which creates a very strange atmosphere in the cultural center of Paris, it was a challenge and an honor and we did it! We each received the Commodore of Fine Arts and Letters from the French Minister of Culture, it’s a dream come true. Only five great artists were selected previous to us, so it means we are considered on the same level. Now, if we could only get something like this recognition in the United States, having lived here for so many years now. It’s about time people understand that we are not only about “communal apartments,” that the “Kabakovian world” is much more complicated, more philosophical and meaningful than it is referred to in Wikipedia.

Long Island, particularly the East End, has been a haven for artists for decades. What drew the two of you to Mattituck and how does the environment of the North Fork influence your work, if at all?

Kabakovs: The North Fork is our home and our heaven. We work here, we live here, we create here and you cannot tell how much this heaven influences you or your work. It’s just there with you, always and everywhere.

|

|

A Kabakov assistant in another of the large studio spaces on their Mattituck complex. (Photo: Kevin D. Morris for Hamptons.com) |

(The documentary “Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Enter Here” by North Fork filmmaker Amei Wallach with Ken Kobland as editor and Kipjaz Savoie as co-producer will screen at the Parrish Art Museum on Sept 25. The film made its New York debut at Film Forum and is currently touring the US and Europe.)