Director Alex Winter offers a riveting look at The Panama Papers, which is largely viewed as the largest data leak in history, in his latest project, The Panama Papers.

Making its World Premiere at the 2018 Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF), the documentary, which Winter produced along with Robert Friedman and Glen Zipper, and with executive producers Laura Poitras and Charlotte Cook, explores the monumental coordination amongst journalists to break the explosive story and the Papers’ wide-spread ramifications, including incriminating 12 current or former world leaders, 128 politicians or public officials, and other notable names.

We caught up with Winter to learn more about the documentary:

When and how did you become aware of the Panama Papers?

AW: I became aware of them the day the story broke – it was a big story. I already have an interest in stories about whistleblowers and types of corruption. I was immediately taken, at first by the magnitude of the coordination amongst journalists – I had never heard of anything like that before. At that time I think it was around 380 journalists from around the world working in secret to break that story. Ultimately I think there were another couple hundred that came on. It did turn out to be the largest act of coordinated journalism, but even at the time it was coming out, it just seemed really compelling to me. Both the breadth of what they uncovered, what that says specifically about global society, and sort of on a micro level, the human story of how. I’ve dealt with stories that have dealt with encryption and the encryption secrecy on a lot of my projects and it’s hard. It’s like how did 400 journalists pull that off? So it was a story I found interesting early on, but it’s such a big leak and there’s so many stories within that leak. I think it took me at least a year to understand and connect the dots and understand what the greater theme of the leak, what the implications were.

When did you start filming?

AW: I got involved in this project a while ago and I didn’t start filming, doing the bulk of my shots, until about a year and half ago. We do a lot of research and archival footage to start and form relationships with various subjects. Then we dig in and do the heavy lifting and I traveled all over the world with these journalists, Panama, Munich, London, all over. But, it was a fairly intense process both because of the level of secrecy we had to maintain and that the story was still going. I was in London shooting at The Guardian when Daphne was assassinated and I had just interviewed Juliette who knew Daphne very well. We covered Daphne up to her death. It hit us pretty hard. It wasn’t like we were in the middle of the group filming as they were breaking the story initially, but we were definitely dealing with heavy implications. We were almost done when the Prime Minister of Pakistan was put in jail. So things are still irrupting as a result.

With so much information included (11.5 million documents) in the Panama Papers, how did you decide what to include and who to interview?

AW: A doc is always about selection and reduction, ultimately. Especially a feature doc, which is primarily what I do. I’m a narrative filmmaker by trade normally and I come at these stories like narrative films. So I’m really focused on what is the narrative arc, what’s the emotional arc, and the job of narrating these stories can’t be mapped out. You can stake them out, but not categorically in advance, you map them out as they’re going. It’s always about trying to focus in on a core and manageable group of characters that the audience can follow. Obviously characters that strike at the heart of themes of the story and have significant relationships to the story. When you’re dealing with a story like this when there were 400 people, I could have interviewed more, but I made a categorical decision to only focus on a handful that were scattered across the globe that could speak to their experience in covering the story.

|

|

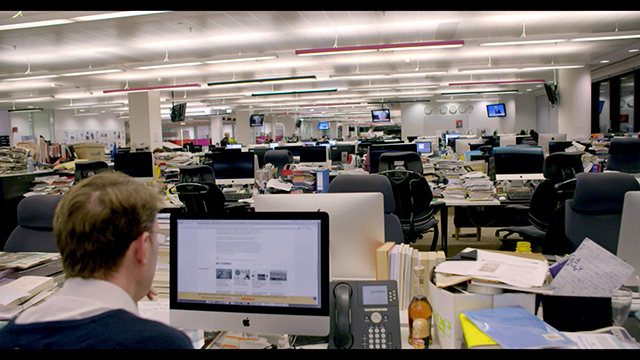

The Panama Papers is considered by many to be the largest data leak in history. (Courtesy Photo) |

As the journalist state in the film, there had been other articles written about offshore accounts, so why was revealing how it works such a big deal?

AW: Because no story had revealed how it worked. What you had before was stories that talked about that obviously the wealthy were hiding their money, obviously they were creating mechanisms and some of these offshoring entities were allowing them to hide taxes. But there had never been a leak of this scope that really laid out the granule system – from a to z of these offshore mechanisms and the sheer breadth – people from Russia, the U.S., Brazil, China, Iceland and on and on and on. Mossack Fonseca had offices all over the world so it was not obviously coming from Panama. There was a law firm based in Panama, but their offices were all over – there was an office in Wyoming. So what you have was a massive paper trail with names, with accounts, with invoices, with internal communications between corporate shareholders and members of Mossack Fonseca, other lawyers, other banks. You essentially had a veil lifted from an entire system and I think it was the first time a lot of people like Jack Blum, Jack didn’t work on the Panama Papers, Jack is a legendary lawyer and financial fraud tax investigator. When we were talking, he could piece together how the system worked, but it wasn’t until he thought about it and said here, finally we have rock solid clarity and evidence about how the system works and what that means is that the watershed for most of these people and why it’s a watershed moment for them is that it allowed them to come to the conclusion that this was an actual systemic issue. What we really have is a system that’s constructed essentially to keep the poor and middle class from having the services and being able to excel and lead more functioning and more liberated lives. That was very new for pretty much everyone I spoke to. Even those that had been dealing with offshore investigations for decades.

What was the most shocking thing you learned from this process?

AW: There was something everyday – it was one of those projects. That wasn’t the first time I’ve been on a project like that, but you get used to opening your laptop and getting an encrypted email that tells you something seismic on some level. There were many things. I’d say globally the most shocking thing was as I was piecing together for myself what I just told you, which I was really seeing up close by going through the data and talking to my sources how systemic this problem was. As I really began to realize the coordination between banks and law firms, laws are being constructed to shield and protect these systems – that was pretty shocking. It’s still outrageously criminal, but that was very, very shocking – the brazenness of that. On a more personal level, there were things like what was happening to the reporters in Russia, what happened to Daphne in Malta, uncovering some of the corruption that was going on there. Dealing with Matthew, Daphne’s son, and Jake who are on the ground in Malta, that was shocking, but personal for me. The other thing that was quite emotional for me was spending a fair amount of time in Panama and really connecting with Rita and Scott at La Prensa and Bobby Eisenmann who created La Prensa – it’s not there anymore – and really getting a sense of how much risk those people took in covering a story and it was a twofold risk because on the one hand they were revealing criminality by a lot of people that they knew – it’s a very small country. That was extremely risky for them and unpleasant and dangerous on a personal level. But also there was a fair amount of prejudice. It was called The Panama Papers, the default implication is that Panama is somehow worse than everyone else and that’s really not true. The biggest offenders of offshore and tax evasion are the UK and U.S., so I really felt for the teams in Panama. I felt like they were getting hit by both sides.

After seeing the film, what do you hope people take away?

AW: When I make a film, I really want people to have an enriching cinematic experience. For lack of a better way of putting, that’s the most important thing to me is that we make a film, it is a narrative and has a narrative drive, and an emotional drive, and I really want people to have a satisfying experience with it and engaging experience with it as a film. I’d say thematically we don’t beat around the bush. This is a film about income and inequality. It’s a film that at the end is saying very concretely that if you as an audience member can wave aside this notion of systemic inequality by saying oh the rich will always get away with it, you’ve been propagandized, you’ve been bamboozled into thinking that something that’s egregiously criminal is okay. Even though there have been laws constructed to keep this legal, it’s deeply unethical and it’s deeply criminal. It isn’t a call to action movie, but we are dealing with an outrageous system of criminality and I do want people understand that of course there’s something you can and should do if you’re being robbed.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

AW: We’re really excited to be premiere with you guys. We’re looking forward to coming up.

The Panama Papers will screen on Saturday, October 6 at 6:45 p.m. and Sunday, October 7 at 7:15 p.m. Both screenings will take place at East Hampton UA1 (30 Main Street, East Hampton). After the World Premiere on Saturday, October 6, CNN’s Don Lemon will moderate a post-screening discussion with Winters.

For more information, or tickets, visit hamptonsfilmfest.org.